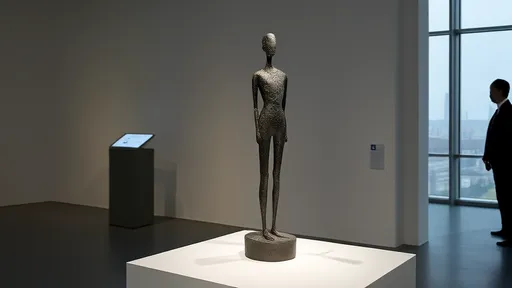

The recent failure of an Alberto Giacometti sculpture to sell at auction has sent ripples through the art world, raising questions about the cooling appetite for Surrealist masterpieces. The piece, estimated to fetch upwards of $20 million, was withdrawn after failing to meet its reserve price—a stark contrast to the feverish bidding wars that once characterized the Surrealist market. Collectors and analysts alike are now asking whether this signals a broader shift in taste or merely a temporary lull.

Giacometti, whose elongated bronze figures have become synonymous with post-war existential angst, has long been a darling of the auction circuit. His works routinely shattered records, with "L'Homme au doigt" (Pointing Man) selling for $141.3 million in 2015. Yet the muted response to this latest offering suggests even blue-chip artists aren’t immune to market fluctuations. "There’s a palpable hesitancy," noted Geneva-based art advisor Élodie Morel. "Buyers are scrutinizing provenance and condition with unprecedented rigor—especially for pieces that aren’t unequivocal icons."

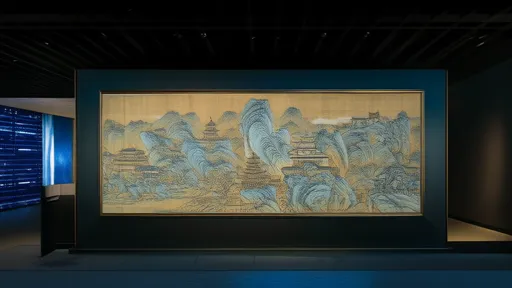

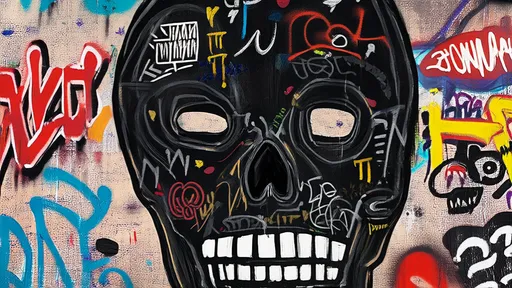

The Surrealist movement, born from the ashes of World War I, once captivated collectors with its dreamlike subversion of reality. Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks and René Magritte’s bowler-hatted men became shorthand for avant-garde prestige. But as contemporary art dominates headlines—think Basquiat’s $110.5 million skull or Banksy’s shredded "Girl With Balloon"—traditional Surrealist works risk being perceived as relics rather than revelations. "Younger collectors want art that speaks to now," argued New York gallerist Marcus Drew. "A 1940s Giacometti might feel like homework compared to, say, a KAWS sculpture."

Market data reveals a telling trend: while Surrealist sales accounted for 8.7% of global auction revenue in 2017, that figure dipped to 5.2% by 2023. Some attribute this to generational turnover. The heirs of mid-century collectors are increasingly liquidating estates, flooding the market with supply. Meanwhile, trophy-hunting billionaires from Asia and the Middle East—key drivers of past surges—are pivoting toward digital art and NFTs. "The psychological landscape has changed," said economist Clara Voss. "Surrealism emerged from trauma and absurdity. Today’s collectors seek either escapist joy or overt socio-political commentary."

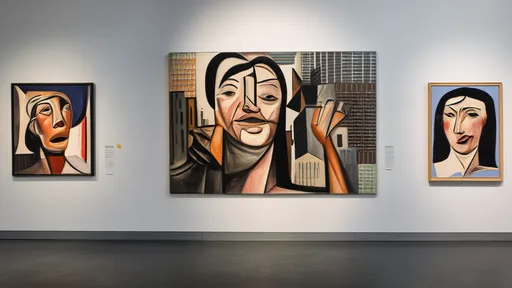

Yet whispers of the movement’s demise may be premature. Private sales and gallery shows still report steady interest, particularly for lesser-known Surrealists like Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning. Moreover, Giacometti’s auction stumble coincided with a broader market correction—one that’s also impacted Picassos and Warhols. "This isn’t about Surrealism losing relevance," insisted Paris dealer Laurent Besson. "It’s about collectors refusing to overpay for anything less than perfection." A recent Sotheby’s evening sale underscored this nuance: while the Giacometti faltered, a Miró canvas soared 40% above estimate.

The question lingers: is this a momentary chill or a seismic realignment? For now, dealers are recalibrating expectations. Pre-auction estimates grow conservative; guarantees (where houses promise sellers a minimum price) grow scarce. "The froth is gone," observed critic Anika Richter. "What remains are true believers—and they’re waiting for masterpieces, not milestones." As the art world braces for its next major test—the May auctions in New York—all eyes will be on whether Surrealism can reignite its old magic or yield to the relentless march of new movements.

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By /Jun 26, 2025

By Emily Johnson/May 21, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 21, 2025